Where the Wildflowers Grow

2023 - 2024

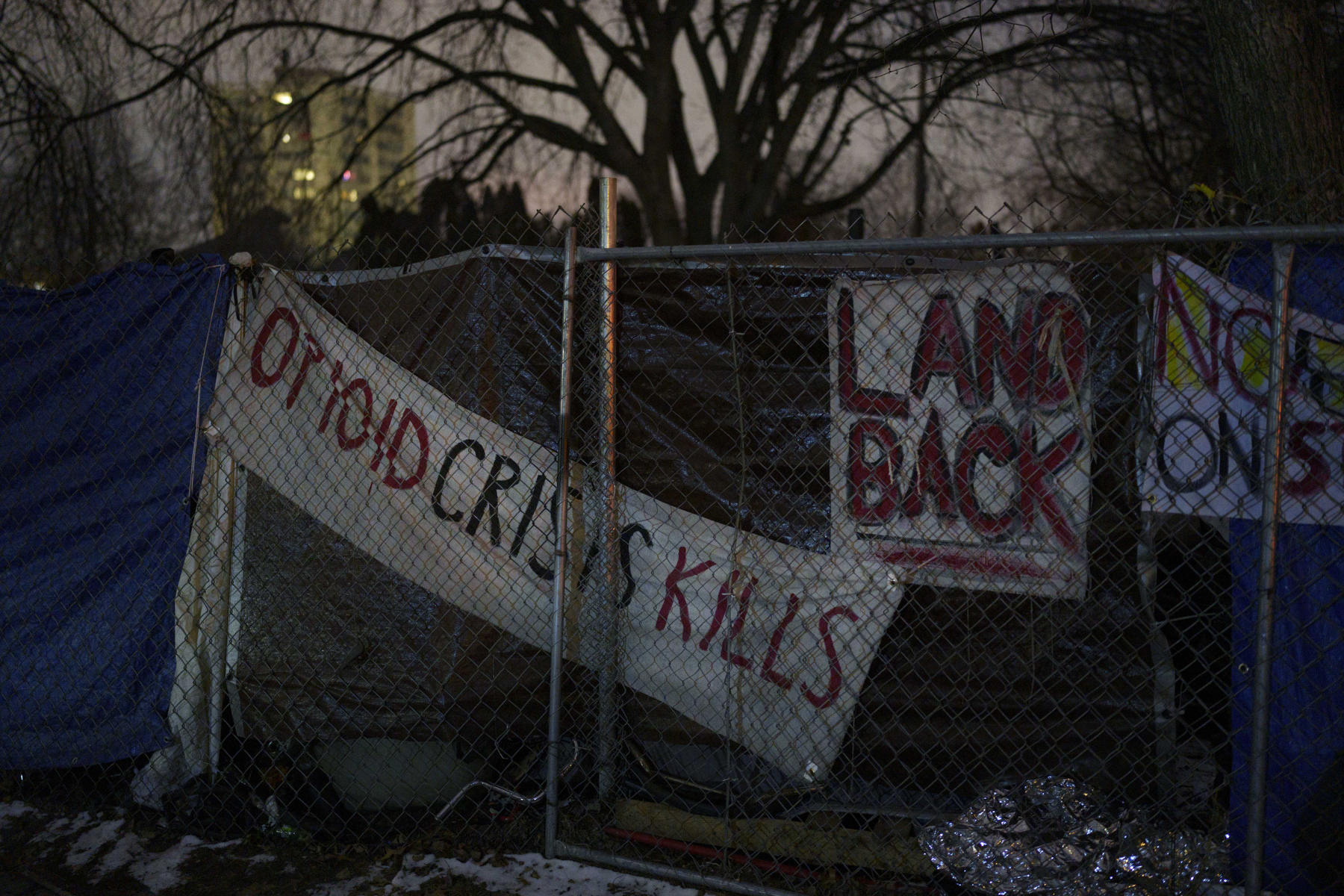

The overdose epidemic kills over 100,000 Americans every year, directly or indirectly touching the lives of roughly 40% of the population. Minnesota, like so many states, has suffered the ravages of this crisis firsthand, with annual deadly overdoses doubling from 636 to 1272 between 2018 and 2023. The recent increases in lethality and harm are a part of the third wave of the opioid epidemic, which began in 2013 and is largely attributed to the ubiquity of fentanyl, a synthetic opioid up to 50 times more powerful than heroin.

While Americans from all walks of life have been caught up in this epidemic, needs vary considerably across the population. Social determinants of health—such as race, wealth, and the strength of one’s social networks—afford a degree of stability that can help insulate substance users against the vulnerabilities faced by those also coping with poverty, criminalization, racial disparities, and homelessness. Unhoused folks feel these dynamics acutely, as they’re approximately six times as likely to die from overdose than those who are low-income and housed. What’s more, the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s 2024 single-night count of unhoused individuals saw an 18 percent year-over-year increase in the number of people without housing. The result is a deepening, intersectional co-crisis between overdoses and homelessness.

Despite the gravity of the ongoing situation, there’s reason for optimism. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention reported in May 2024 that overdose deaths decreased by a shocking 10.6 percent nationally between April 2023 and April 2024—a drop closely mirrored by Minnesota’s statewide decrease of 11.5 percent. This marks the largest decline in overdose mortality in decades, by a wide margin.

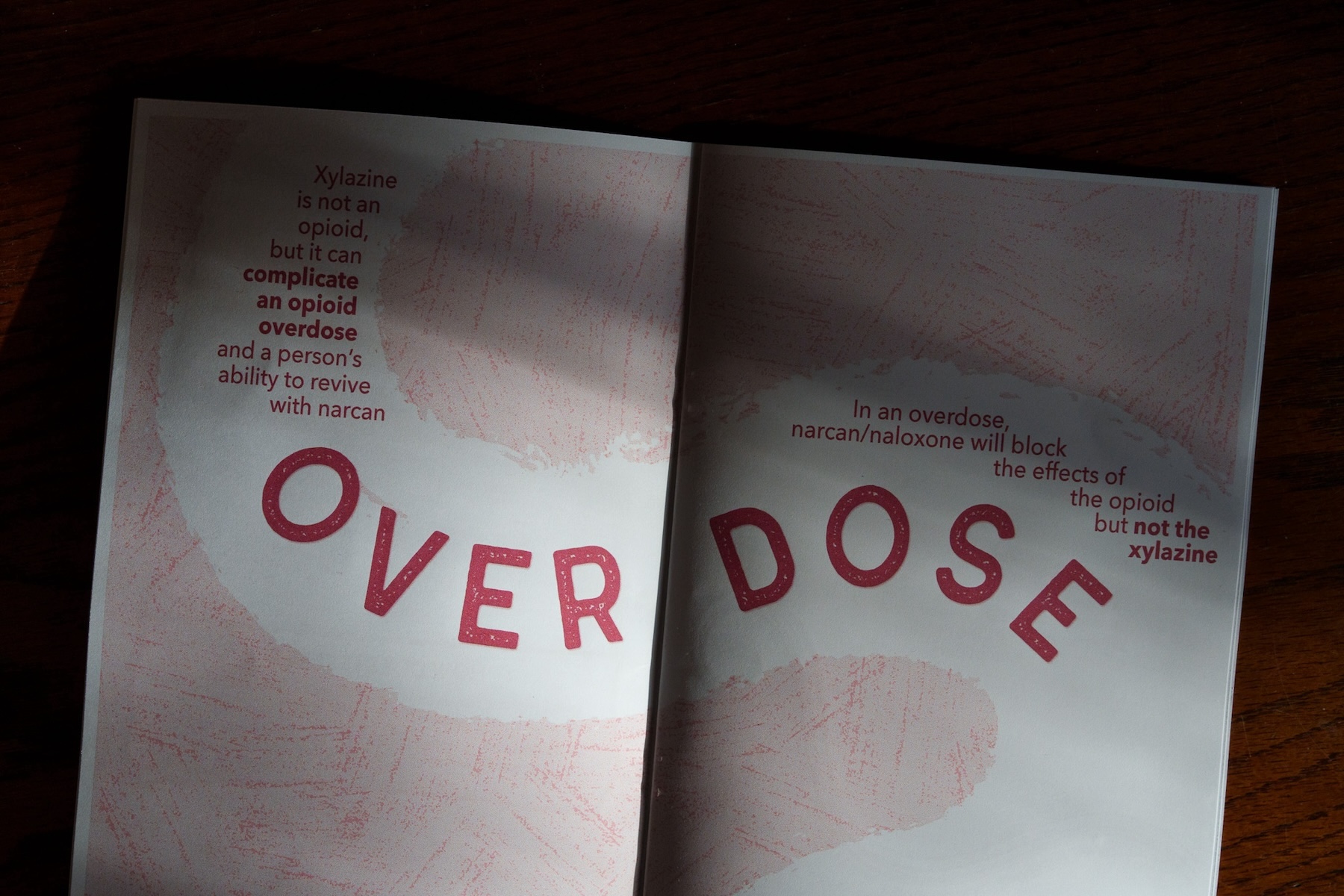

Experts say a variety of factors drive this unprecedented decrease: users’ growing familiarity with fentanyl, more accessible treatment, and a tightening of the drug supply. Another vital factor is the growing implementation of harm reduction, a set of practices proven to mitigate the known risks associated with drug use and other behaviors. While aspects of harm reduction have been gradually folded into mainstream health infrastructure, much of the work continues to be spearheaded on the street level by grassroots communities of often current and former drug users dedicated to supporting their peers. For many such advocates, the approach is viewed as much more than a public health intervention; it’s a way of life that serves as an antidote to entrenched social, racial, and class inequalities.

Where the Wildflowers Grow offers an intimate look at Minneapolis’s grassroots harm reduction movement as advocates work to support communities during a time of overlapping crises.

An excerpt from this project along with a feature article were published in The Nation. This story was also co-published and supported by a grant from the Economic Hardship Reporting Project. An interview about the work was broadcast on MPR News' Minnesota Now.

“I’m native and in Minnesota we have the worst overdose death rate disparities in the country. Native Minnesotans are dying at a rate that is more than 11 times that of white Minnesotans. And there are similar numbers for Black Minnesotans too. Those numbers and experiences are just not okay. And so I see harm reduction as a way to work against some of the colonization and acts of colonization that have happened and to improve the health and wellbeing of any communities--of all communities--in Minnesota.”

- Jack Martin, co-founder of Southside Harm Reduction Services

“Medically assisted treatment providers are still barely catching up with how to treat substance use disorders and people who use drugs. There’s still a lot of stigma and lack of understanding across the board, even from medical providers who are trying to be on the cutting edge. There’s just [scientific] papers right now, for the first time, that are talking about how different levels of dosing for things like suboxone or buprenorphine interact with fentanyl users. These are crucial, life-saving treatments for users, but we’re just now getting to the point where people know how to treat fentanyl.”

- Zach Johnson, program director at Southside Harm Reduction Services

“There’s proven practice to reduce harm, and yet people don’t let [others] access it. It’s just really maddening. Because harm reduction has been around forever. It is the way that we take care and look out for one another. If someone’s sick, we take care of them. And that can be applied into so many worlds. But when it comes to drug users, when it comes to sex workers, when it comes to people living with infectious diseases, such as HIV or hepatitis C, it’s all hands-on-deck to block it off. And it’s because the government literally created a war on drugs, which is just a war on people. It’s not on the drugs. It’s on the people using them.”

- Marissa Bonnie, harm reduction health educator at Native American Community Clinic

"Putting people in housing is harm reduction. I’m in a program called housing first, it’s GRH--group residential housing. I’ve got my own apartment. I have hardly any money, but I don’t care. I have a place to live. And for me, I’m not going behind dumpsters in alleys. I’m not risking that, you know. I don’t violate my lease, and I've been in the program for over 10 years now. Stability is huge.”

- Rick Kooy

"I want people to be alive, I want people to be healthy, and I want people to be safe. To know they have a community with them. That no matter where you’re at in life, there’s going to be someone around to support you."

- Shannon Clancy, the education and overdose prevention lead at Southside Harm Reduction Services

“[Southside Harm Reduction's] logo is prairie grass and wildflowers. In terms of ecological renewal after disasters, the first things to grow back are usually grass and wildflowers. They offer a very specific role in the regrowth of an environment. The grass and wildflowers bring nutrients to the soil, help stabilize the soil, and allow for bigger things to grow—bushes and eventually trees and then the rest of the forest. I hope that Southside can take on that role within Minneapolis and Minnesota.”

- Jack Martin, co-founder of Southside Harm Reduction Services

____________

A special thanks to the participants who made this project possible, particularly the folks at Southside Harm Reduction Services.